In 2017, a terror group known as Ansar al-Sunna or Al-Shabaab had taken a foothold in the oil-rich northern region of Mozambique, having met no resistance from the country’s forces.

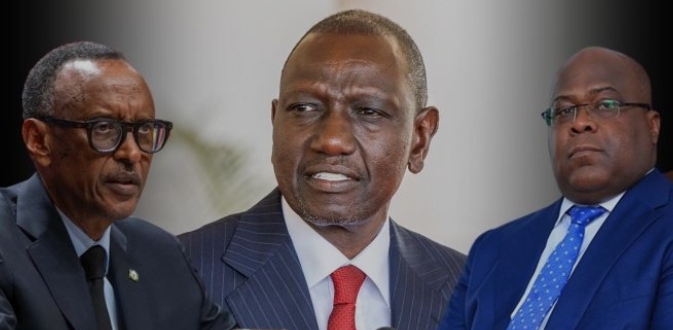

However, following the intervention of Rwandan forces, JOEL MUKISA writes that normalcy has been restored, albeit with some civilian casualties.

For years, African countries have turned into a ferment of international terrorism, casting countries into the global limelight as security agencies across the unstable continent seem to be at sixes and sevens on how to foil the attacks.

A case in point was in Southern Africa, where ISIS partnered with an Islamist group called al-Shabaab (no link to al-Shabaab in Somalia) and took a foothold in Mozambique, where it staged attacks in the northern Cabo Delgado province, chasing away the presence of the central government as well as the local population.

The violence, including the raiding of villages and towns, had killed more than 3,306 people and displaced at least 800,000 from their homes over the years, but the assault was halted when Rwanda sent about 1,000 soldiers. Rwandan troops, according to the agreement the East African nation signed, took responsibility for three districts: Palma, Mocimboa da Praia, and Ancuabe.

The contingent, the Rwandan Security Forces say, is divided into two components— military and police—with a Level II field hospital. On August 8, 2021, Rwandan security forces said that, jointly with Mozambican forces, they had captured the port city of Mocimboa da Praia.

“The joint forces captured several major towns, trading centres, and villages, including the strongholds of Mbau and Awasse, along with other key areas such as Naquitengue, Chinda, Diaca, Quelimane, Pundanhar, and Nhica do Rovuma in Palma, Mueda, and Mocimboa Da Praia city,” Rwandan forces said.

Though instant success was registered by the time Rwanda intervened, the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the regional bloc to which Mozambique belongs, had filibustered on its pledges to contribute troops. South Africa, the most powerful country in the bloc, said it couldn’t fulfil its commitment because of what it termed “organizational and logistical” reasons.

The operations to eliminate terror groups in Mozambique are under the auspices of the United Nations, or UN, and the African Union (AU), which prompted many to question whether civilians would be protected during this period.

Formerly, traditional peacekeeping missions had an unacceptable record of protecting innocent onlookers. The UN and AU were criticised for failing to protect citizens in South Sudan, DR Congo, and the Central African Republic as atrocities were carried out under the watch of the peacekeepers.

As an offensive counterterrorism operation, the mission is also hypothetically more aggressive and violent than peacekeeping, but findings have shown that Rwanda hasn’t used a heavy hand in putting down the rebellion. The Rwandan army, according to Ralph Shield, who has done extensive research on Rwanda’s operations in Mozambique, inflicted its first recorded civilian, a single curfew breaker, in a tensely recovered town.

“Rwandan military behaviour in Mozambique operationalizes Kigali’s rhetorical commitment to aggressively defend endangered civilians.

“The counterinsurgency doctrine applied in Cabo Delgado balances insurgent pursuit and civilian protection through a combination of contact patrolling and tactical restraint,” Shield says, adding that this formula demonstrates learning from the country’s previous experience with domestic rebellion and international peacekeeping.

One of the tactics Rwandan troops have used to ensure that Mozambique citizens are won over is actively patrolling and interacting with the community to collect information about the local people and the insurgents who threaten them.

“Rwandan soldiers benefit from their knowledge of Swahili, which enables them to communicate directly with the locals. It helps them tell friend from foe,” Shield says, adding that the second factor is restraint: a more disciplined use of firepower, but he hastily adds that the experience of Western armies in Iraq and Afghanistan has shown that maintaining restraint under the persistent threat of ambush isn’t easy.

The fact that Cabo Delgado is the location of a liquefied natural gas project run by French energy giant Total has only triggered questions about what exactly Rwanda’s intentions are, but now there are also questions about when these troops will pull out.

This is not an easy question when you factor in the fact that Mozambique had failed to overwhelm the jihadists in the years before the foreign troops arrived.

“The Islamist insurgency in Mozambique, however, has yet to be defeated. A long-term solution will require more fundamental political and social measures, as well as reform of Mozambique’s security services,” Shields says, adding that Rwandan army operations have demonstrated what a competent African force can do when properly resourced and committed to the mission.

Rwanda Defence Forces publicist Brig Ronald Rwivanga recently said that the foreign forces had fulfilled their combat and security missions, and now they are making arrangements for internally displaced people to return to their homes.

“In the Palma and Mocimbona da Praia districts, the returnees are about 80 per cent, and the number keeps increasing as more people begin rebuilding,” Brig Rwivanga was quoted by the East African in December 2023.

Credit: JOEL MUKISA Via The Observer

![]()